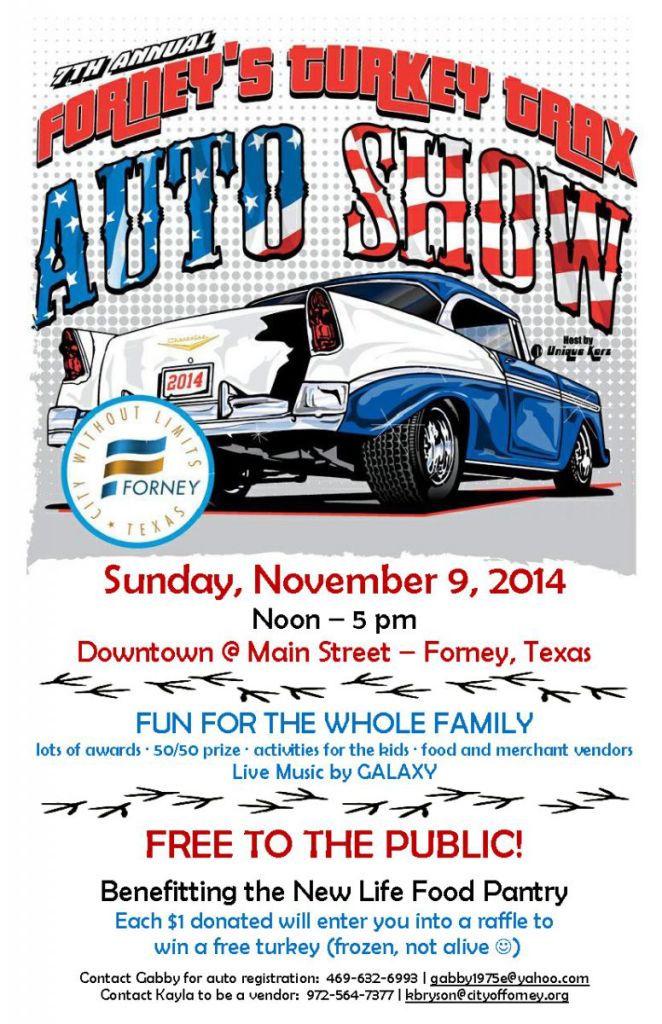

Early voting has started in Kaufman County as Forney is set to select 2 council candidates, 2 school board candidates, and a new mayor. Early voting runs through Tuesday, May 5th with election-day voting on Saturday, May 9th. If you attended either of the candidate forums held last week, you got a chance to hear from most of the candidates and form an opinion as to how you’ll vote.

Forney first elected a mayor and city council in June 1884, approximately ten years after its founding but having just been incorporated. At that time, the city government was a mayor and several Aldermen. It didn’t last long. The officials elected in 1890 were never seated due to a technicality. In Forney Country, Jerry Flook describes city government from 1890 to 1895 as being “in a state of flux”. Then in September 1895 the city charter was abolished by popular vote, and there was no city government at all.

So what happened in Forney with no local government? A group of men called the Forney Commercial Club took it upon themselves to run the business of the city. They acted essentially as boosters: recruiting businesses to town, encouraging improvements and beautification projects, and establishing basic utilities such as water, electric, and sewer systems. They were able to do so in part by raising money from family, friends, neighbors, and businesses. During their tenure they re-shaped downtown Forney – literally.

Forney’s first commercial buildings relied on the railroad for transportation of supplies and the export of agricultural goods. Businesses and gins were built close to and facing the tracks since most of the activity occurred on the railroad side of the building. But beginning in 1899 a dramatic shift occurred as new businesses were built between the streets of E. Main & E. Trinity and S. Bois d’Arc & N. Elm (still our central business district) with entrances to Main. Existing businesses relocated their primary entrances to face the street as well, including Tom Layden who had built the first brick structure facing the tracks. There is no official reason why this happened, but it seems to have been a trend of the times since other area municipalities noted the same shift. Although some of the buildings have burned or otherwise come down, most of downtown Forney as it stands today was built between 1899 and 1910.

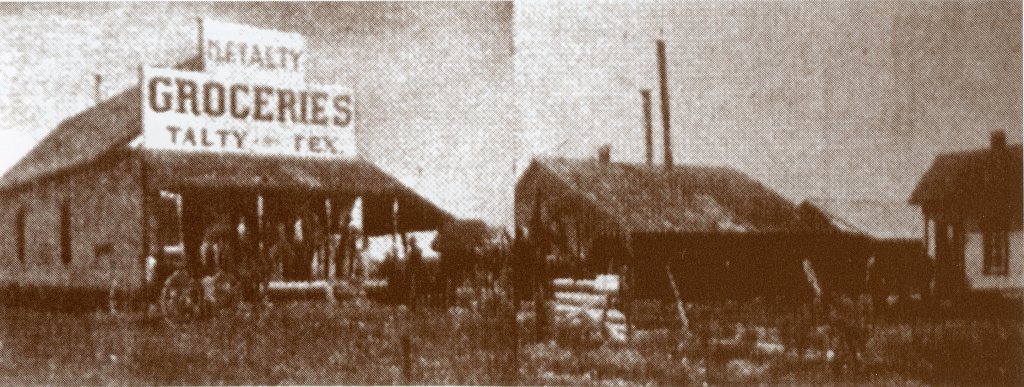

Downtown businesses in 1889 facing the railroad tracks. This is Front St. (or the back side of Main St. depending on how you look at it).

Layden building, 1899. You can see this at far right in the picture above. Although this shot was taken from the tracks, this is around the time that Layden added on to the building in the rear to make a new entrance on Main St.

In 1909 the Commercial Club was instrumental in developing Forney’s water supply and raised funds to drill a new artesian well. The need for a steady water supply had recently become tragically apparent due to a drought which dried up the ponds needed to operate the cotton gins and a deadly fire which broke out in the City Hotel near the corner of S. Bois d’Arc and W. Front streets. In fact, the drilling had struck water a few months before the fire, but the distribution system had not yet been completed. Needless to say, that become a top priority and was in place by summer of that year.

Also in 1910, members of the Commercial Club petitioned to Kaufman County commissioner’s court to set an election to reincorporate the city of Forney with a new mayor, council, and marshal. Naturally the slate of candidates consisted of Commercial Club members, all of whom were elected. Forney selected as mayor Avery Duke, as marshal Robert Crawford, and as councilmen Richard Pinson, John M. Lewis, James Cooley, Yancy McKellar, and James C. Reagin. Since these men had essentially been running the town for the past 15 years (with others), it was a pretty smooth transition.

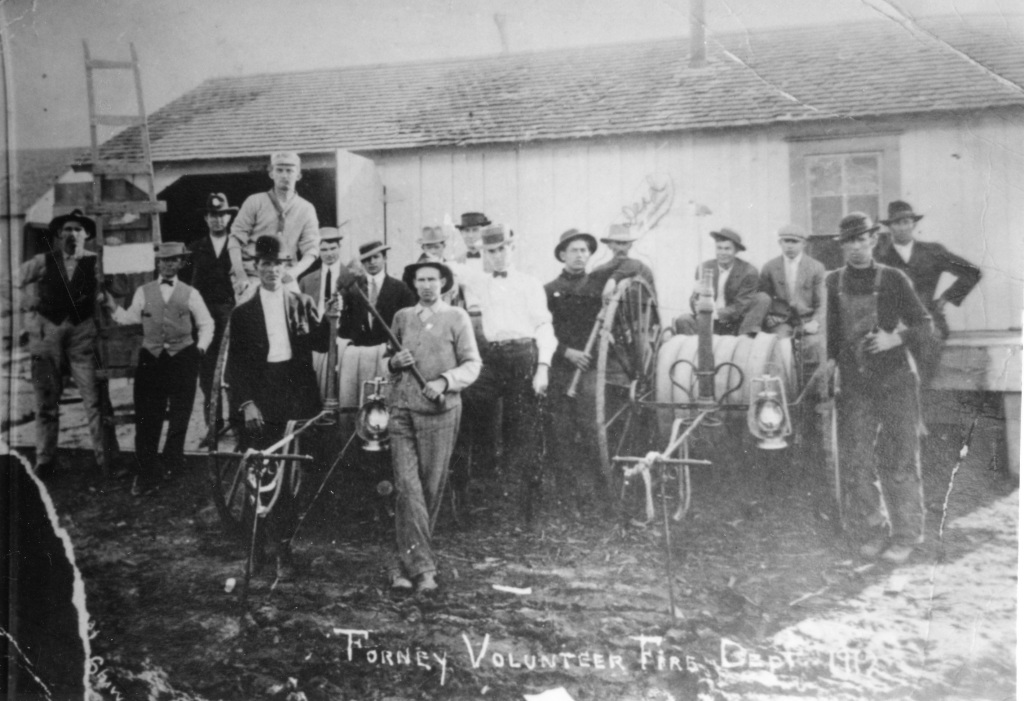

Building on the success of the water system, one of their first acts as a council was the organization of a volunteer fire department. The first fire chief was J.E. Yates, and the VFD was ready as soon as the water distribution system was complete. Their first call was on July 11, 1910 when two houses in two different parts of town caught fire. One was saved while the other was lost, but the community was pleased with their efforts.

Volunteer Fire Department, 1912. This is on Trinity St. before the brick fire station was built at Trinity and Bois d’Arc in 1913.

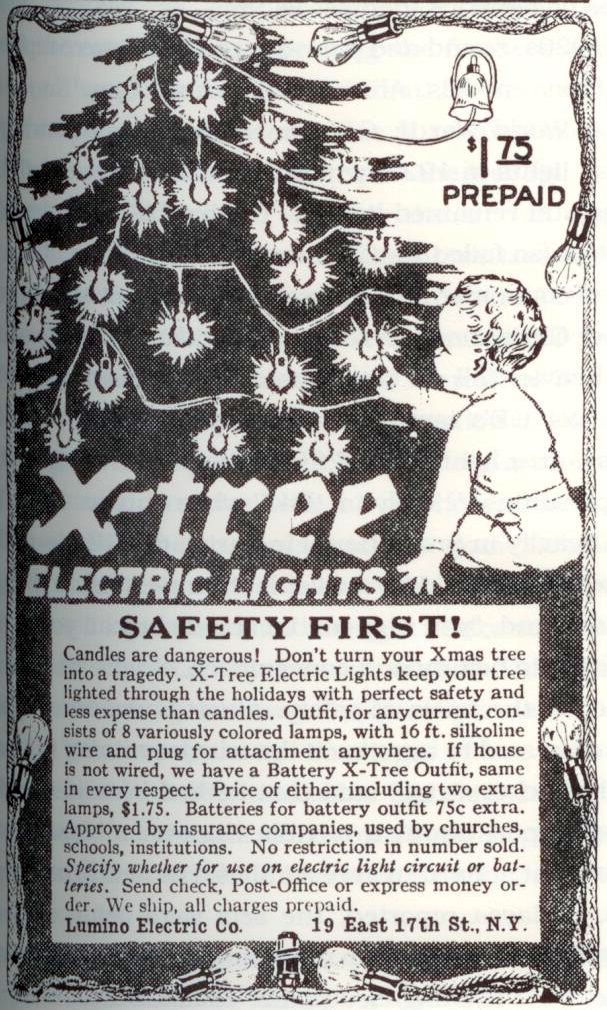

A water supply also made possible electrical service in Forney since the electrical generators were steam powered. The Forney Light and Ice Company was privately owned and was built in 1910 for $25,000. Its construction was rapid, as was the wiring of businesses and homes. Electric lights hummed in Forney for the first time on August 12, 1910.

As you can see, 1910 was a busy year here. In about 6 months Forney was reincorporated with new officeholders, completed a downtown overhaul, received water and electric service, and organized a new volunteer fire department. It could be considered the beginning of “modern” Forney, and the town boomed for the next 20 years or so until crop prices tanked in the 1930s.

It seems as though Forney is in the middle of another big boom today. The population is rising, the number of schools has grown three-fold in the past few years, and construction is trying to keep pace with both retail spaces along 80 and housing developments a little farther south. Voting in local elections is a way to voice your opinion about how Forney manages its growth and continues to prosper. So take the time in the next two weeks to go do it.

Thanks,

Kendall

Information about the election and polling places can be found here.

As always, we’d love to hear from you on our facebook page.

![100_3537[1]](https://historicforney.org/spellmanmuseum/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/100_35371-225x300.jpg)

![100_3540[1]](https://historicforney.org/spellmanmuseum/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/100_35401-300x225.jpg)