The museum is decorated inside and out for Christmas. The FHPL had its December meeting and Christmas party last weekend, and many more holiday parties are to come. I’ve been late with my shopping this year, and I barely decorated my house for Christmas. I wouldn’t call myself a Scrooge or a Grinch, but I still think of Christmas as a holiday centered on children. Since I don’t have any, I tend to tune out a lot of the season’s spirit. It’s the same for my sister. She works at Walmart where Christmas decor was out before Halloween was over. They’ve been playing Christmas carols on a loop over the loudspeaker for weeks now. Working Black Fridays for 10 years or more will drain just about anyone’s Christmas cheer.

It’s easy to decry the over-commercialization of Christmas and reflect on the “good old days” when times were simpler and people understood the true meaning of giving. But I’ve got news for you: Christmas has been commercialized in America for a long time.

In one of my college classes we studied a book called “Merry Christmas!” by Karal Ann  Marling. It explores the materialism of Christmas in America dating back roughly to the 1830s and how some of the traditions of contemporary Christmas got started. It has chapters titled “Wrapping Paper Unwrapped”, “Window Shopping” and “Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town” in an attempt to explain, among other things, how Santa came to hawk Coca-Cola in the 1930s and shredded wheat and fountain pens as early as 1902. (Marketing hint: Santa sells!)

Marling. It explores the materialism of Christmas in America dating back roughly to the 1830s and how some of the traditions of contemporary Christmas got started. It has chapters titled “Wrapping Paper Unwrapped”, “Window Shopping” and “Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town” in an attempt to explain, among other things, how Santa came to hawk Coca-Cola in the 1930s and shredded wheat and fountain pens as early as 1902. (Marketing hint: Santa sells!)

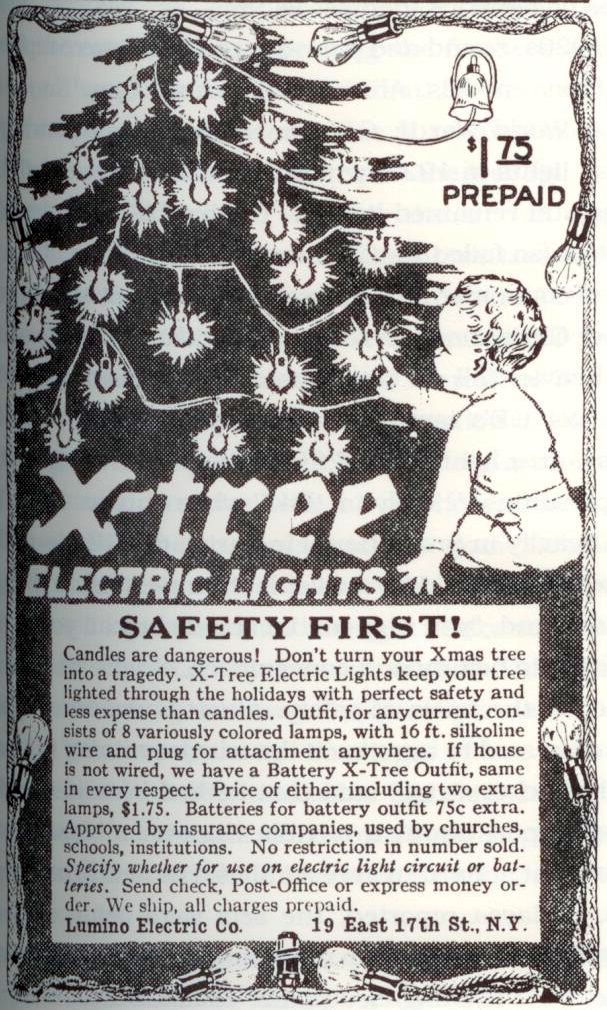

Marling calls Santa a “captain of industry” for his effect on consumption. Way before Black Friday was a common phrase, several industries relied on the month of December to sustain their businesses. The lumber trade profited by selling trees and greenery. Railroads and other shippers were busiest in December because they transported not only the trees but commercial goods whose sales peaked near Christmas. Entire industries like candy, toys, and perfume blossomed based on December sales alone. In the 1890s, strung electric lights were one of the first industries tailor made for the holiday; they touted the safety of electrical lights over candles, gas lamps, and other open flames near trees.

Gift wrapping has ties to the commercial nature of the holiday, too. In the 1860s, wrapping presents was essentially unknown. Smaller gifts and candy were “trimmed” on the tree and hung like ornaments while larger or heavier gifts simply lay nearby. Parents dressed the tree late Christmas Eve so the kids were surprised by the gifts in the morning. This gave the appearance that Santa had delivered the presents overnight. In many cases the tree itself wasn’t erected until Christmas Eve since it essentially was just the method of delivery for the children’s presents.

As early as the 1870s, most gifts nationwide were purchased, not homemade. When you bought something, the store bundled everything up in brown or white paper and tied it with twine. Rather than unwrapping everything and putting it under the tree, gifts were presented as they left the store – bundled and tied with twine. The act of pretty-ing up a package a bit with a nice bow, ribbons, holly, or other decorations was an attempt to mask the fact that the gift was purchased. The giver sought to add a personal touch to a store-bought item by decorating it differently. Gift wrapping arose as an attempt to diminish the commercial nature of the Christmas present. Of course it didn’t take long for companies like Hallmark to start designing and selling wrapping paper, thus commercializing something intended to cover up commercialization.

Even Christmas trees, Marling argues, can be viewed as signs of conspicuous consumption. As already mentioned, the tree was the display piece for the gifts. It was a showpiece of presents, sweets, candles, and in later years ornaments, tinsel, and electric lights. It was a dramatic spectacle of bounty. People hosted Christmas parties to show off their trees and bestow gifts. They placed them in front of windows so that everyone walking down the street could see their trees and the gifts underneath. Department stores and other groups erected large and elaborately decorated trees to increase traffic and, thus, business. Public and government buildings also erected trees as a symbol of the wealth and health of its citizens. All of this in contrast to the earlier tradition – filling stockings hung by the hearth. For most of the 19th century, stockings and trees were competing traditions. Stockings are a lot less showy, you must admit. No sparkling lights, no garlands or ribbons. You don’t need gift wrap when you’re stuffing presents in a sock.

So if you really want to embrace the spirit of Christmases of yore, don’t wail against the consumerism of the holiday – embrace it! Christmas has been an American celebration of materialism for over 100 years! Deck the halls, feast and be merry! And when you finish your Christmas shopping, drop some money in the kettle as you leave the store or adopt an angel from the Lions Club tree to spread some joy to those who have conspicuously less to consume.

Thanks,

Kendall

Post your Christmas memories on our facebook page.

The book:

Marling, Karal Ann. Merry Christmas!. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2000.