If you read the Forney Messenger, you saw Don Themer’s article on the Forney Cotton Oil and Ginning Company that operated in the first part of the 1900s. I had learned about the mill and other early industries in Forney as I researched the history of the town when I began working at the museum. As I read Don’s article, though, it occurred to me that I wasn’t really sure what cottonseed oil was or how it was used. My grandmother may have picked cotton in the fields of northeast Texas, but my city/suburban upbringing insulated me from knowing exactly how food and fiber crops are grown and manufactured into the products in my house. So please humor me as I try to educate myself on at least this one subject.

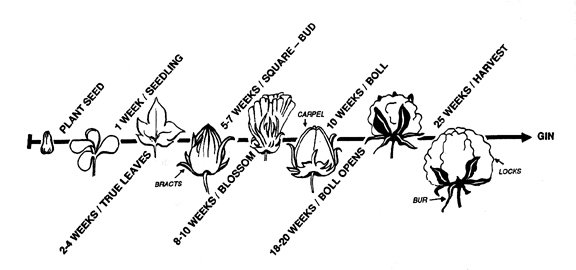

First, a primer on cotton itself. From a seed the cotton plant progresses from seedling to bud to blossom, as most plants do, after which the blossom falls away to expose a closed green boll. Inside this boll are the seeds and fibers which gradually mature until the fibers grow so large that the boll splits open.

The lock is not all fluffy and soft, however, because the seeds are in there, too.

Separating the seeds from the fibers is a difficult and time consuming process if done by hand, which is why everyone learns about Eli Whitney in school. Ginning uses rollers to separate the fibers from the seeds. Although Whitney didn’t invent the process (people had been ginning cotton in India and China for centuries), the gin he patented included “teeth” or combs which enabled mechanical ginning on a much larger scale.

The fiber, of course, is processed into textiles and other things. But what happens to the seeds? For a long time, nothing. Some was used for planting or animal feed, but cottonseed was considered a useless byproduct that was a nuisance to dispose of. When animal fat and whale oil became scarcer and more expensive to purchase in the 1850s, some enterprising businessmen tried to develop cottonseed oil by crushing the seeds. But cotton is stubborn and makes you earn everything you get out of it, and so, of course, it was very difficult to separate the seed meat from the hull. By the time a reliable huller was invented, cottonseed oil was able to enjoy only a brief year or two of use as lighting oil before it was replaced by new petroleum products.

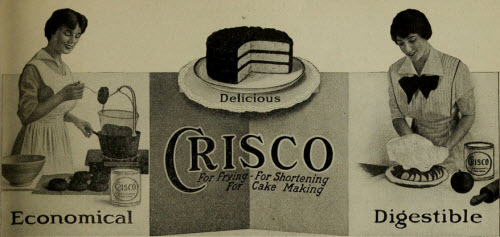

A new company called Proctor and Gamble began buying cottonseed oil as a supplement for lard in its candles and soaps. P&G bought so much it essentially cornered the market. With the onset of electricity, however, candle sales dropped dramatically, leaving the company with a lot of cottonseed oil and not much to do with it. Its engineers expounded on the edible liquid cottonseed oil that Wesson Oil had developed years before and hydrogenated it to create a solid lard substitute. Crystallized Cottonseed Oil, trademarked Crisco, hit store shelves in 1911 accompanied by a vast marketing campaign which included cookbooks (with Crisco in every recipe) and eventually radio cooking programs.

Cottonseed oil became the most popular plant-based oil in the United States and was used as an ingredient in mayonnaise, salad dressings, and other products in addition to its main use as a cooking oil. But as cotton prices dropped during the Great Depression, farmers switched to other crops. When cotton production declined so did cottonseed oil, and soybeans took over the top vegetable oil spot in the 1940s.

But the possibility of a resurgence lingers. Cottonseed oil is cheaper than other products like canola and olive oil and is thus gaining popularity in processed foods. And as with any other food these days, specialty organic cottonseed oil producers are entering the mix, like this company which offers flavor-infused varieties. Others have begun converting cottonseed oil into a biofuel like ethanol. Only time will tell if that will prove profitable. Still, it’s come a long way from a useless byproduct, no?

Visit the National Cottonseed Products Association website for more cottonseed facts.

Share your thoughts on cotton, cotton gins, cottonseed oil, or any other subject on our facebook page.

Thanks,

Kendall